THE CREEK AND THE ROAD

Recollections of a Former Resident of The Hollow

Part I

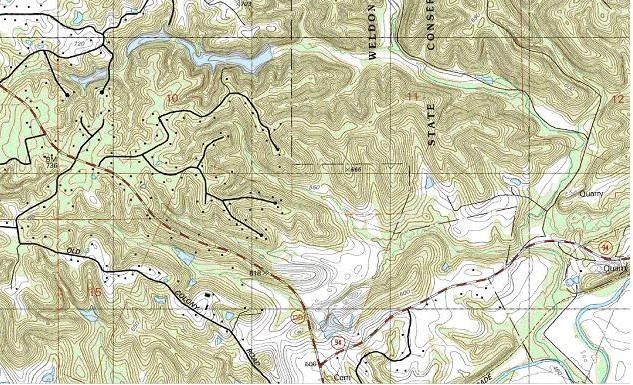

A two-dimensional map doesn't give a good idea of the way the Little Femme Osage Creek made its way down from its many spring sources through "The Hollow" — or why the road ran alongside it and across it and through it the way it did. To really understand, it takes a topographical view — a three-dimensional picture of the hills and valleys, clefts and forks, ridges and gorges and branching creek tributaries.

A section of the USGS Defiance Quadrant map. Defiance is located to the left of the area shown; before 1941, the town of Hamburg was to the right. The Hollow is on the right side of the map, along the Little Femme Osage Creek.

It is terrain that made “The Hollow” what it was, creating its secluded character as a little world all to itself. Terrain shaped the way the waters flowed together, and only terrain can explain the meandering pathways that later became roads, and still later, the trails of "Lost Valley" in the Weldon Spring Conservation Area.

In the early 1930's, anybody wanting to enter the Hollow coming from Hamburg or Defiance would turn off Highway 94 into the place that is now the Lost Valley Trail parking lot.

From there, one would ford the creek to a lane that led to the first farm house in the Hollow, on the left. This is where our neighbors, the Gravemann family, lived. Their daughters helped our family with the housework when they were young. When I was old enough to go to school, my mother would walk with me down to their house, and from there I walked with the younger Gravemann children to the Calamus Spring School.

To enter our own valley, we turned right, into the creek, and went upstream in the water about 500 feet. The creek then veered sharply to the right, and the road came out of the water and ran to the left, along the edge of the Gravemanns' large field on the western side of the valley.

My recollections are from about 1932 to the middle of 1937, when I was ten years old. That was a time of hot summers and very limited rainfall. The stream never ran completely dry in this place, but there were other, shallower places where the water thinned to a trickle, leaving the creek's small fish stranded in isolated shallow pools. We would scoop them up in tin cans and run to put them back in the creek where the water was deeper. Small as they were, they were our neighbors too.

This part of the road turned to dust in the summer's heat. Snakes from the field would cross the road to reach the water in the creek, leaving their tracks in the dust.

I actually saw a three-foot long black snake crossing the road late one afternoon, when my brother and I were coming back from school. We both started to scream, and our mother came running out from the house down to the creek. Because the water was deepest here — seven or eight feet, at that time — she was understandably afraid that one of us had fallen in and was drowning.

Near the boundary between the Gravemann and the Keller farms, the road ran close alongside the foot of the steep hill that rose up from the far side of the Gravemanns’ field, forming the western wall of the Hollow. Where the creek curved sharply back toward the left, meeting the road, it enclosed a little field, just two acres, more or less, between itself and the right side of the road.

This field was used by my grandfather for planting "sugar cane," as it was called, a tall thin corn-like grass from which they made sorghum molasses. We children were not allowed to be nearby while the molasses was being made, but we helped by picking up driftwood from the creek that the men could use as fuel to keep the kettles boiling.

Past this little field, a short driveway off the road to the right was the entrance to the Keller farm, our home. The farm was divided into two parts by the creek, with the house, barns, and animal enclosures all on the northeast side.

The house stood about a third of the way up a hill, facing west, with a vista from its porch over the valley. A well nearby provided excellent tasting water for the household. There was also a spring on this hill, behind the old cemetery of the Muschany family, who had owned this land and built the house in the mid 1800's. We used this spring to keep our butter cool, and to chill watermelons on hot summer days.

Our cows grazed in the meadow near this spring, and its outflow made a little stream from which they could drink during the day. The mules got their drink directly from the creek after their day's work, before their tack was taken off and they were led into the barn for the night.

We crossed the creek on stepping stones, when we were on foot, to get from one side of our farm to the other. Across the creek, the road continued along the base of the great hill on the southwest parcel of the farm, where wild blackberry bushes grew in profusion. I remember picking berries there with my mother and brother. Some of the fruit grew higher on the bushes than a child could reach (and some that we could reach didn't make it into the pails we carried).

There was another small spring on that hill that was used by friends during times of severe drought. Those whose cisterns were running low would bring barrels to fill at the spring whenever they needed water.

When the road reached the end of our 40-acre field, it made a right turn to cross the creek again, and led from there across the narrow valley to one of the hills that formed the valley's eastern wall. An African American schoolhouse stood on the right side of this section of the road, overlooking the creek. It was not open during the time that I remember.

After our family moved away in 1937, a new road was built through our farm on the east side of the creek, to replace the road that had run on the west of it. A drain pipe was installed where the small stream that flowed down from the cows’ meadow met the main creek. This made travel through the Hollow by car and on foot much easier than it had been before. The west branch of the Lost Valley trail system follows this newer road, which lay entirely on the eastern side of the creek.

The road continued on up the hill, past the spring described by Don Muschany in his book The Rape of Howell and Hamburg, Missouri (An American Tragedy):

To see several photographs depicting life in "The Hollow" in the 1920's and 30's, click here.

Part II

Just beyond the end of the big corn field on the Keller farm, the Hollow Road again crossed the main branch of the Little Femme Osage Creek. Then it turned right to go across the valley to its far side, running parallel to a tributary branch of the creek that joined the main stream a short distance above this sharp bend.

If you continued going straight alongside the creek, after crossing this tributary you would come to the home of Mr. and Mrs. Smith. Going still further upstream would bring you to the Muschany family farm.

I remember little about Mr. and Mrs. Smith. Their home was across the creek from the abandoned African schoolhouse, and could not be seen from the road. I was told that they had both been born into slavery, so they were quite elderly in the mid-1930’s.

After the Hollow Road left the main creek, it led toward the hill that formed the valley’s opposite wall. This hill was owned by our other Black neighbors, Uncle Louis and Aunt Addie Scott. In the middle of the valley, the schoolhouse stood by itself on the right side of the road, just past the boundary of our big corn field.

When it reached the base of the Scotts’ hill, the road made a sharp turn to the left. Here it was met by a path from our house that ran at the side of our corn field along the base of the hill.

A few feet past its turn, the road crossed the stream beside which it had been running since leaving the creek on the other side of the valley. This stream was fed from a big spring on the Gockes’ land.

The Gockes lived in St. Louis, but during the time that I remember, their niece, Mrs. Bassett, and her husband were living in the big house overlooking the Hollow Road.

Like our farm, this farm was also divided into two tracts by the creek and the road. Before the Gockes bought it in the 1930’s, it had been “The Hiler Place,” and prior to that, Richard and Laura (Bacon) Johnson had owned it. Laura was my grandmother Cora Keller’s sister, and the mother of TNT area landowner May Dell (Mrs. Dennis) Pitman.

On one of our walks, Mrs. Bassett invited us to see the spring, which flowed from a cave that was large enough to stand up and walk around in. She said we could go inside the cave, but I was just as happy to view it from the entrance.

She told us that they had built several small dams downstream from the cave, to form small pools that were to be stocked with fish. In time, this is what happened.

After leaving the area of the cave and spring, the road passed the house where the Bassetts lived. At the end of their place, there was a driveway to the right that led up the hillside to three weekend cabins. This was the Villiers’ property. Just past this driveway, at the bottom of the hill, the road crossed the main creek again.

Beyond this point, the valley widened considerably. Here, on the Muschany farm, the Hollow Road turned off to the right, while a driveway leading to the Muschany family farmhouse ran straight through the middle of this spacious area, making two large fields in front of the house.

My mother’s best friend, Aunt Daisy Sutton, had grown up on this farm with her five brothers -- Bob, Bill, Ed, Louie, and Waldo (“Pat”) Muschany. Mrs. Muschany, her mother (we called her “Grandma”), lived in the main farm house with three of her sons, and Aunt Daisy and Uncle Vernon lived with their daughter Dolly in a small cottage behind the main house.

When we went to visit them, we walked from our house along the path at the foot of the Scotts’ hill, and then along the Hollow Road; this was also how we went when we walked to Howell.

(When we took the car to Howell, we drove on Highway 94 through Hamburg and Toonerville to the road that was later replaced by present-day Highway D. We never took the car on the Hollow Road.)

In front of the Suttons’ home, to the left, were a meadow and a hill that Dolly had to cross on her way to Calamus Spring School. To the right, there was a long narrow valley that channeled the biggest tributary in the Little Femme Osage watershed system.

The spring origin of this branch of the creek (which we considered the “main” stream) was in the far western end of this narrow valley, near the farm on Old Colony Road that belonged to St. Louis merchants Bill and Sallie McKenney, my paternal grandparents.

(In the 1970’s, the western end of this branch of the creek was dammed, flooding part of the valley to form lakes for recreational fishing.)

Water in this branch of the creek flowed east, along the north side of its long narrow channel, toward its confluence, on the Muschany farm, with the true “main” stream running down from the north.

From the point where it had branched off from the Muschanys’ driveway, the Hollow Road continued across the valley for perhaps another quarter of a mile, before beginning its long climb up the hill to Howell.

A short distance above the valley floor, there was a meadow to the left. It was here that Mr. Kaut, who worked for the Brown Shoe Company in St. Louis, built his beautiful rock house. We heard that he called this area “Hidden Valley.” His property was not destroyed when the TNT area was developed, and after the area was decommissioned, we were told that it became a Boy Scout camp.

The road continued on up the hill, past the spring described by Don Muschany in his book The Rape of Howell and Hamburg, Missouri (An American Tragedy):

Leonard Kessler, the well driller . . . was a man of many talents. He bought

a certain piece of property behind Howell on the Hollow Road that had a

spring that never went dry; it came out of a small cave on a hillside. Mr.

Kessler built a concrete dam just below the spring and there was always a

refreshing drink for a thirsty traveler in a beautiful setting. . . . Just about

any evening, at dusk, you would find Mrs. Kessler and one or two of the

girls taking a walk. Not because they lacked exercise, but because they

enjoyed looking at nature. [p. 230-231]

The overflow from this spring crossed the road, cascading to the valley below, and its waters became part of the Little Femme Osage after meeting with the main stream at a confluence point a bit north of the Muschany farm.

At the top of the hill in Howell, the Hollow Road passed the home of Uncle Erwin (“O. E.”) Bacon and Aunt Lulu and their children, who were neighbors of the Kessler family. Uncle Erwin was my grandmother Cora Keller’s brother. One of his daughters was Eslie (Mrs. Arch) Howell, whose husband and brothers-in-law were also TNT area landowners.

The road then continued on to Howell’s Main Street, where we would shop at the Muschany Brothers’ store.

I remember one trip, walking to the store in the winter with my mother and brother. While we were shopping, it started to snow. By the time we reached home, we had been trudging through ever deepening snow for what seemed like hours. We were drowsy from the cold, but Mom kept us talking so we wouldn’t fall asleep. I thought we would never reach home.

Part III

The bed of the Little Femme Osage Creek was quite large, with its gravel bottom and high banks. There was always water in its branches, though not very much during the ‘30’s because of limited rainfall during those years. Of course, the Missouri River flooded every spring, backing into the little waterways, but that didn’t ever impact our part of the stream.

Recent satellite imagery of the area indicates that the water courses are much the same now as they were in the ‘30’s (except where dams have been built to form fishing lakes), but the volume of water is generally greater now than it was in the years when we could cross “our” creek on stepping stones.

There was only one time that I remember a flooding incident. That day, Dad met my younger brother and me on our way home from school, leading our mule Jenny. He told us the creek was too high for us to cross, so he put us both on Jenny’s back and led her across the flood waters. Earlier that day, there had been a storm up on the prairie, and though not a drop of rain had fallen at our farm or at the school, the creek had risen and its current would have swept us off our feet if we had tried to cross it.

(That day came to mind years later when I was driving through the Arizona desert and saw road signs warning motorists to watch for flash floods from rainstorms in the mountains, miles away.)

When it came time for me to start school, I was told I would not be permitted to attend the school that stood at the edge of our big field. Instead, there was a choice between Hamburg School, where my mother had been a pupil (and where her cousin LaVerna Fridley had once been a teacher), and Calamus Spring School, which was at an equal distance from our home in the opposite direction.

The schoolhouse at the edge of our field had been built for African-American children to attend, and it had been closed for years. When I asked my mother where the children lived who were supposed to attend that school, she told me that their families had moved to Hopewell.

To get to school when she was a girl, my mother used to walk through the orchard behind our house, down the hill to the little valley that led past the Wackhers’ home (the Richters’ home during the 1930’s, and the Oberle place on the TNT-era map), then past the path that led to the Bowman family farm, and from there up the hill to the highway (“94”). Hamburg School was further up the highway on the far side, at the northeast corner of its intersection with the road to Lower Hamburg.

My grandfather also walked along this same route almost daily, when he went to town to pick up the mail for our family at the Hamburg Post Office. After passing the Richters’ place, he would cut across the large field where the Fridleys (his sister’s family) pastured their cows, and come out on the highway beside Seib & Wackher’s store.

One day, walking along that path, my mother pointed out the way to the home of Aunt Dene Bowman, whose son Archie is honored with a monument in the Thomas Howell Cemetery as the last American soldier killed in World War I. I was also told where Archie’s uncle, Ben Bowman, had lived, in a little log cabin at the southeast edge of our farm. He died the year I was born, so I never met him, but his brother, Uncle Frank, came to visit us quite often—he and my grandfather would sit together on the porch and talk for hours.

Aunt Dene’s brother, Charlie Schustoff, was also my grandfather’s friend. Whenever he came to visit on a Sunday, he was always invited to stay and join us for dinner.

As we walked along the path to Hamburg, Mom showed me the places where morel mushrooms grew (secret places that one must never reveal to anyone), and she pointed out some of the wild flowers and ferns that grew there. I also learned from her to watch the ground vigilantly for snakes (if a stick ever moved . . . !).

I was not yet five years old when I started school. My parents chose to send me to Calamus Spring rather than Hamburg because the other children who lived in our valley were going to Calamus Spring. In the morning, my mother would walk with me down the road to the Gravemann farm (the Oberdick property on the TNT-era map), and the Gravemann’s daughter Viola would take me the rest of the way across the fields with her. The following year, her little brother Arthur joined us in our walks to and from school.

On our way, we had to cross through a fenced field on the Tylers’ farm, where a bull was pastured. Grown-ups would tease us by saying how fierce and scary that bull was, but fortunately he never seemed to care, or even notice, that we were invading his territory.

When I started school, Uncle Bob and Aunt Nettie Muschany were living on a farm between the Gravemann home and Calamus Spring. Since they lived closest to the school, their oldest son Lloyd would go early and get the fire going in the school’s pot-bellied stove, so it would be warm when the teacher and the rest of the students arrived. After Lloyd graduated from the eighth grade, his brother John Edward took over the task of making the morning fire.

Because I was absent for more than two weeks during my first year at school, I had to repeat the first grade. Miss Lucille Sanders was my first teacher; after she left, Miss Alberta Bay was the teacher. We did our lessons at school on hand-held slates, and for our homework, we used lined paper tablets with red covers that we bought at Seib & Wackher’s store. The tablets had a picture of an Indian chief on the front cover.

I carried my books, a pencil box, and a metal lunch box to school in my satchel every day. Dad made my lunch in the morning—two meat sandwiches and a butter-and-jelly sandwich—from bread that Mom had baked and butter and jelly that she had made, and thick slices of pork from our own hogs, butchered on our farm. For our beverage, we had water from the school’s cistern, which I drank from a collapsable metal cup that I brought in my lunch box. During the winter months, our teacher encouraged us to bring potatoes to school and put them in the stove ashes to bake in the morning, so we could all enjoy a hot treat with our lunch at noon.

There was always a picnic on the last day of school, with lunch provided by the students’ parents. The food was served on tables made of planks laid on sawhorses, covered with table cloths. More people came to the picnics than just the parents of students at the school. We would have a program in the morning, and games in the afternoon—three-legged sack races, races carrying eggs in a spoon, and the like.

After we moved to St. Louis in the summer of 1937, Calamus Spring School was closed, because the school district would not keep it open just for the two children from our valley who would still be going there in the fall. So the families of those children had to move. One of them, Dolly Sutton, transferred to Hamburg School, and Arthur Gravemann’s family moved to the district that was served by Walnut Grove School.

Part IV

Our family home was a large, two-story building that stood about a third of the way up the hill that formed the eastern wall of our valley. The oldest part of the structure had been built of logs by German immigrant Edward Muschany, sometime in the mid-1800s. He and his family were laid to rest in a small fenced plot overlooking a steep ravine behind the house. In keeping with European tradition, the Muschanys planted an evergreen tree to stand as a landmark over that sacred ground.

As of this writing (2012), that tree, a spruce, is over 130 years old, and it still holds its place in the cemetery, healthy and beautiful. Another evergreen tree, a lofty cedar, was also a landmark while it stood in the yard south of the house -- its top was permanently bent during the terrible winter storm that covered everything in a thick coat of ice on the day I was born.

As of this writing (2012), that tree, a spruce, is over 130 years old, and it still holds its place in the cemetery, healthy and beautiful. Another evergreen tree, a lofty cedar, was also a landmark while it stood in the yard south of the house -- its top was permanently bent during the terrible winter storm that covered everything in a thick coat of ice on the day I was born.

The doctor who came that day, Carl Bitter, had his medical practice in Defiance. He was German, and his wife made soft little pillows as gifts for all the babies he brought into the world. Mine was a doll, with embroidery to depict the face and hair, and I had it for many years. When my brother was born, his gift from the doctor’s wife was a little pillow horse.

The farm had belonged to my grandfather, John Keller, since 1888, the year he turned 21. That same year, he married his cousin, Cora Bacon, and went to St. Louis to earn money. He made enough to fill the house with fine furnishings, among them a walnut dining room suite (a table and twelve chairs, breakfront and sideboard), Louis XIV-style parlor furniture, an oriental carpet, and a baby grand piano, which he shipped to Hamburg by train. He never left the farm again to make money, and we joked that he “retired” at 21, though of course, he still had all the farm work to do.

The oldest (log) part of the house consisted of two rooms, one on the ground floor and the other above it. It had been enlarged with a two-story frame addition at the back, containing the central hallway with its staircase to the upper floor, the parlor, and the bedrooms upstairs. A one-story extension ran nearly the full length of the north side of the building, encompassing the kitchen and the dining room. The root cellar, with its hinged door in the floor, lay under the kitchen.

My brother and I slept in the upstairs room that was part of the original log structure. But when my mother was a girl, that space had been used by her parents as a ballroom for parties and gatherings of their neighbors and kin. Music on those festive evenings was provided by the host himself, playing his fiddle, and by friends who brought their instruments along, like Currier Fridley, his sister Ines’ husband. For the last dance, the musicians always played “Good Night, Irene,” and the guests would then make their farewells, wake up their horses, and start home.

Mom met her future husband at one of these dances. Bill and Sallie McKenney, his parents, were newcomers to the area, having moved from St. Louis to a farm on Old Colony Road (now Highway DD north of its intersection with Old Colony Road). Among their new neighbors were the Lays, the family of John Keller’s sister Pearl. The Lay girls were quick to invite the McKenneys’ son Gilbert to attend a dance at their Uncle Johnny’s home. Soon after that first dance, he began to ride his horse down the Little Femme Osage valley to visit his new friend Rose Keller, who soon became his fiancee, and then his wife.

The Kellers had a spring wagon and a buggy with isinglass windows, but Dad’s parents had an electric car and a convertible touring car as well — and by the time he was married, he had a car of his own. Cars were comparatively rare in the area at that time, and seeing one usually meant a visitor was coming from out of town.

From our front porch, and from the swing on a limb of the big oak tree beside it, we had a fine view overlooking the hills to the west and the Hollow Road that ran through the valley beneath them. While I was swinging, Grandpa Keller would sit on the porch steps and smoke his pipe.

Once when I was swinging, the two of us saw a car drive up the valley, and after a short while we saw it return again. Later that day, Grandpa got a phone call from the neighbors about the “nice young man” who stopped at their farm to ask how to get to Kansas City from there. It wasn’t until after he drove off that they realized the lost motorist was a man whose photo they had seen on a “Wanted” poster in Hamburg — the notorious gangster, “Pretty Boy” Floyd.

Another day on the swing, I saw a cigar-shaped airship floating down the valley. Grandpa told me it was a dirigible, taking people on a sightseeing excursion. It was kept moored at Lambert Field in St. Louis; this was long before the 1937 crash of the Hindenburg at Lakehurst, New Jersey put an end to the use of passenger-carrying airships.

Because of the danger of fires, especially in the hot dry summers of the 1930’s, people were accustomed to scanning the horizon throughout the day for signs of smoke. One spring evening, just before bedtime, my brother and I were called into the back yard to look at the sky. It was alive with undulating sheets of light, dancing in a way we had never seen before or since (except in movies). But those sheets of light, shining with so many colors, were not fire — it was the aurora borealis of May 29, 1932, making a rare display in our area.

At the south entry to the house, in the downstairs hall, stood an organ and a player piano, with rolls of Broadway show tunes for our entertainment. We also had a gramophone with wax cylinder recordings, and some evenings, Dad would take the battery out of his car and hook it up to the radio, so we could listen to broadcasts from WGN in Chicago.

We heard Big Band music from Chicago’s Starlight Ballroom, Admiral Byrd’s broadcasts from the South Pole, and the execution of Bruno Hauptmann for the kidnapping of the Lindbergh baby. Though his trial had been held in New Jersey, there was a great deal of local interest in the “crime of the century,” because of Lindbergh’s connection with St. Louis from the time of his celebrated non-stop flight across the Atlantic.

The big front room downstairs, Grandpa’s room, had as its source of heat a cast-iron stove. Its pipe ran through the ceiling into the upper room, and the radiant heat kept us warm there at night in our beds. The telephone hung on a wall near the great bedstead; there was a chest of drawers, a rocking chair, and a bookcase absolutely packed with good things to read.

I remember the books by Jane Austin, Zane Gray, and Mark Twain. When Dad read my brother and me a bedtime story, as he did from time to time, it might be a chapter from Tom Sawyer or Huckleberry Finn. There was a beautiful set of encyclopedias, a dictionary, a Bible, an almanac, and a set of hard-bound National Geographic magazines that I dearly loved — for giving me a glimpse of the vast, fascinating world that existed outside the confines of our little valley.

On the north side of the house was a concrete porch, accessed through a door that opened outward from the kitchen. Firewood, eggs, and water from the well were brought in from the yard through this door. Our chicken houses (two of them) stood across the yard — the house where they laid their eggs was opposite the kitchen door, on the north side, and the one where they roosted at night was on the east. Nearby were the smokehouse and the building where Grandpa stored his tools. The rain barrel stood behind the house, in an alcove formed by the dining room’s east-facing wall, and the well and pump were in the northwest corner of the yard.

Our hogs lived in a rail-fenced enclosure at the base of the hill on which the house stood. It was a short walk from there to the barnyard, with its large barn and corn crib at the south edge of our corn field. The mules, Jack and Jenny, when not at work, spent their days in the barnyard, and our Jersey cows, May and Blackie, were milked in the barnyard morning and evening each day.

My daily chores were feeding the chickens, gathering the eggs, bringing in water from the pump, helping with the dishes, watering the houseplants, and taking care of the canaries. The entire house had to be swept with a broom every day, and a carpet sweeper applied to the parlor carpet. Baking, laundry and scrubbing the kitchen floor were weekly tasks with which I helped my mother, while my brother’s job — an important one — was to keep our baby sister entertained. Once a year, all the dishes were taken out of the cabinets and given a thorough washing, and the carpet was carried outside and beaten clean.

Shortly before Grandpa’s fatal accident, I started to learn to milk the cows and tend the mules. When Dad was teaching me, I did the milking, and he made sure their udders were really empty. They never seemed to mind that I was a beginner. Since I was too short to reach the backs of the mules, I groomed the places I could reach with the currycomb and brush, and Dad took care of the parts I couldn’t reach. They never moved or flinched, even when I was working on their legs. They were so gentle, I think they knew they were helping to train me, even when I had to practice driving them pulling the spring wagon.

Part V

Working animals — cows and mules, hogs and chickens — were a constant presence in our daily lives. Wild animals played a smaller role, and were not nearly as abundant then as they are today.

The Keller farmland is part of the present-day Lost Valley Trail, a designated bird-watching “hotspot” visited by people who share their sightings through the Audubon Society, the Cornell Lab of Ornithology, and other birding organizations. Back in the ’30’s, few people talked about the wild songbirds that could be heard all around our woods and fields — but everyone knew about the “chicken” hawks that had to be kept from snatching a hen out of the farm yard.

We had our two pet canaries, and some of our neighbors had pet birds as well. From time to time, my brother and I would get to go with Grandpa Keller when he visited his friends. On one of our walks, he took us along the path at the edge of our cornfield and on up the valley to the Muschany farm. While Grandpa visited with the adults there, we got to visit with Grandma Muschany’s big green parrot, Polly.

We knew that the bird had quite a vocabulary — but though we both stood before her cage, repeating “Polly want a cracker!” over and over, her only response to this babbling was silence and a sideways stare from her great black parrot eye.

Grandma Muschany told us about the trick Polly liked to play on her sons Bill, Ed, and Louie. Every day at noon, Grandma would call “the boys” to lunch by ringing the large farm bell and calling their names. If there was ever a problem at the house while her sons were out in the fields, she would do the same. Polly could imitate her voice exactly . . . and began to call the boys whenever she wanted. After running up from the fields to the house a time or two, the brothers soon realized that only one of them should make that trip, if they heard their mother calling at any time other than noon.

We weren’t the only ones to use that path beside the cornfield. One summer evening, about 5 o’clock, our black-and-tan hound hunting dog left the back porch, trotted down to the path, and started to bark. We could follow the sound of his voice, noting that he was going into the field, back to the path, into the field again, returning to the path, finally becoming quiet and coming back up to the porch to eat his supper and settle down for the night.

He repeated this pattern night after night that summer, playing “chase” for a half hour or so with his friend, a wild rabbit. The rabbit could have put an end to the whole episode any time he wanted, just by crossing under the fence between the path and the base of the hill. But he must have enjoyed the game as much as the hound did. I don’t know what happened to their relationship — the dog never brought the rabbit home.

That dog was a real hunter. In the winter, when neighbor men came by the house with their dogs to go night hunting for raccoons and opossums, he would be allowed to go out with them. Some of those night excursions were training sessions for Uncle Bob Muschany’s young hounds, so they could learn to “tree” an animal. And when people came out from St. Louis on weekends to hunt on our property, he would get to go with them as well. Rabbits and squirrels were the animals most often sought on the daytime hunts.

One of our most welcome weekend guests was Art Simpkins, a native of England who had fought with Teddy Roosevelt’s Rough Riders in the famous Battle of San Juan Hill. He came out with his wife Della (and sometimes with one or two of their teen-aged nephews), and he always dressed in formal hunting attire — canvas duck jacket and close-fitting pants, with leather gaiters and high leather field boots. On these country visits, the Simpkins family became good friends with Uncle Bob’s family, as well as with my parents. After we moved to the city, we found an apartment not far from where they lived, and continued our friendship with them for many years.

People who were serious about fishing in our area went to the river (our creek had only minnows, used as bait). I never went on any hunting or fishing trips, but I did get to go frog hunting one night. After it got dark, the group went quietly down the creek with a powerful flashlight. When a frog was mesmerized by the light shining in its eyes, someone would capture it with a “gig.” As soon as the adults were satisfied with the catch, we all returned to the house for a meal of fried frog legs.

I have heard that there are white-tailed deer in the area now, though we never saw a deer in “the olden days.” Likewise, beaver have taken up residence fairly recently, and the stumps resulting from their dam-building activity can be seen among the saplings in the flood plain by the creek. In the 1930’s, there were no beaver, but muskrats lived in the low ground along the river, and they were trapped for the money their pelts would bring.

One of my most memorable encounters with an animal happened with an old horse that was brought to our farm to live out his final days in our little meadow. After school, my brother and I would stop to pet him as we passed the meadow fence. One day, when we climbed on the fence to pet his nose, he presented himself alongside the fence, instead of poking his head over it as he usually did. It was just too tempting for us to refuse to mount him.

(We had absolutely no experience riding horses. Our grandmother, Cora Keller, had owned a riding horse named Babe, but when I was young, the animals we had were mules, and they were there to pull equipment, not to ride.)

I clung to the horse’s mane, and my brother clung to me. Once we were aboard, the horse slowly walked up the meadow to a tree with a branch that was barely higher than his back. We could have reached the branch, but there was no way to get down from it, so we both just slid off the back of the animal. We then ran back to the fence to see what the horse would do.

He turned around and walked slowly back to the fence, presenting himself sideways so we could mount again. We repeated this several times before realizing our mother would be wondering why we hadn’t yet come back from school. We never tried to ride the horse again (and we had tried it only because we thought he was inviting us to ride him). A few weeks later, he was found dead in the meadow. His body had been removed by the time we came home from school that day.

Another day, just before school, we found a goat standing at our back yard gate. Mom didn’t know anyone who had a goat, so we gave it some food and a bucket of water to keep it from straying, and while my brother and I went off to school, she started to phone the neighbors about the lost animal. A couple of calls was all it took for the operator to take up the search herself, and by the time we returned from school, the goat had been reunited with its owner. We kids weren’t told who had come for it, or how far the goat had wandered from its home.

We had a chance to see more exotic animals one summer in the mid-1930’s, when the circus came to town. The “Big Top” was set up in a field between Toonerville and Hamburg. Given my terror of snakes, the costumed performer who sat in the snake pit, letting snakes slither all around her, made a huge impression on me!

Some years before (long before I was born), Grandpa Keller had become friends with a couple that traveled with a circus. As I recall the story, Charlie and Kate Baker were camping on the Little Femme Osage (near the present-day parking lot at the entrance to Lost Valley Trail), and went to the nearest farmhouse to ask if they could buy some eggs. The people there told them they didn’t have any extra eggs, but suggested they go up the creek and ask at the Keller farm.

They did, and that was the beginning of a very long friendship. For years afterwards, the Bakers came to visit whenever their circus was in the vicinity, and Charlie wrote letters to the Kellers from various places where they stopped, and also from their winter quarters. When they finally retired from their travels in the early 1930’s, the Bakers bought a small confectionary on Manchester Avenue in St. Louis, where we visited them after we had moved to the city.

Charlie Baker had been the caretaker for two of the circus elephants (he was not their trainer). One story he told was about what he would do to comfort the elephants during severe storms. He slept in a hammock in their quarters, between the two anxious animals, so each one could wrap its trunk around his arm. This always helped the elephants get to sleep.

When they came out to the farm, Charlie and Kate would help out with the work of the day. Elsewhere on this website there are several photos of Kate taken in the early 1920’s — picking blackberries on our hill one summer day, proudly holding a pail of fresh-picked vegetables, helping in the autumn to gather nuts in our walnut grove. And there is a picture of Charlie and Kate together, standing by the split-rail fence around our pig yard; Kate is leaning over the fence to feed the pigs.

Part VI

The pigs we raised on the farm were the primary source of the meat we ate every day at every meal.

Piglets were born in the late winter, and the arrival of the “little pork chops” was a newsworthy event. In 1926, the year my parents were married, Grandpa’s sow gave birth to eight piglets late in the evening of February 21. That night, one of the newborns crawled out of the nest and froze to death, and this unfortunate accident, discovered in the morning, was sure to have been talked about in the local area, as well as shared in letters to relatives and friends.

As winter began to give way to spring, the adults would begin to go over the seed catalogue and the almanac and plan how the garden behind the house should be laid out. Though small in size, the garden was carefully planted to yield a great variety of produce from only a few rows.

I recall the old saying that potatoes had to be in the ground before St. Patrick’s Day. The seed potatoes, bought from Seib & Wackher’s store in Hamburg, were first cut into pieces, making sure each piece had an “eye.” At least three eyes were planted in each hill. Straw would then be scattered over the seed bed to keep the young plants warm.

Early in the spring, before any garden plant had come up, we would go down to the banks of the creek and gather the edible greens that grew wild there — dandelion, wild lettuce, poke, and dock — which we ate as a salad with the best dressing I have ever tasted, Mom’s “secret recipe” involving a warm mixture of eggs, vinegar, bacon grease and sugar.

The first garden plant to come up was asparagus, and soon afterwards, the first tender lettuce leaves would be ready to eat. When the tomato and pepper plants came up, the nights could still be quite cold. We put mason jars over the seedlings in the evening, and then made sure they were removed in the morning to keep the young plants from getting too hot during the day.

Cutworms were a problem for the young cabbages. To combat these pests, we used the waste from Grandpa’s chewing tobacco (collected from spittoons in the house) on each plant — an eco-friendly pest management technique that has been rediscovered by some modern gardeners.

In May, we had morel mushrooms, a wild delicacy which Grandpa foraged from a “secret” place in the woods not far from our house. They were dipped in egg, rolled in flour, and then sautéed in our all-purpose cooking medium, bacon grease.

Behind the house was an orchard with apple, peach, cherry, and red plum trees, and a single damson (prune) plum tree grew in the yard. After the trees had flowered in the spring, they had to be treated with a foul-smelling sulphur spray, to insure that insects would not harm the developing fruit. The flowers were pollinated by a colony of bees that lived in a hollow tree at the edge of the orchard.

In the summer, the garden plants needed to be watered, and in the hot dry 1930’s we were fortunate to have a source of good water so close by. Grandpa would carry buckets full of water from the well to the garden for us, and then my brother and I would scoop cans full of water onto each thirsty plant.

The garden rewarded our hard work with a bounty of fresh vegetables for the table and for canning and pickling: green and white onions, leaf lettuce, radishes (red and white), tomatoes, eggplants and cucumbers, peas and string beans (we called them “pole beans”), carrots and parsnips, celery, spinach, green and red peppers, sweet corn, muskmelons (canteloupe), crook-neck squash, cauliflower, cabbages, beets, rutabagas and turnips, and white and sweet potatoes.

Blackberries were ripe around the 4th of July, and blackberry cobbler, made with the berries we picked on our hill across the creek, was a special summer treat both for us and for our guests from out of town. Guests were served slices of watermelon, harvested hot from the field the day before and cooled overnight in the little spring behind the house, and hand-cranked vanilla ice cream, made for them from our cows’ fresh milk.

Most of the milk from our cows was sent in steel canisters by train from Hamburg to Pevely Dairy in St. Louis. From the milk we kept for our own use, Mom made our butter, churning the cream and molding the sweet residue into one-pound blocks with a rosette on the top. We also made our own cottage cheese.

Mom made watermelon pickle in the summer; for sweet and dill pickles, she would take some of the finger-sized cucumbers from the vine, leaving the rest to grow big enough to become slicing cucumbers. She made her own “kraut” from the cabbages, and sometimes we enjoyed a unique and delicious turnip kraut made by Aunt Nettie Muschany (I think the ladies traded jars).

When the string beans were ripe, I remember getting inside the “tepee” formed by the bean poles to pick the long green pods. Some of the beans were “canned” (put up in mason jars) for the cellar, but the sweet peas were always eaten fresh — at least I don’t recall that they were ever canned. Corn was served fresh from the field, shucked and boiled for only a minute or two . . . or even eaten without being cooked at all.

A grape vine near the garden gave us fruit for jelly, and we had gooseberries, rhubarb, and just enough strawberries for a few pies every summer — though for preserves, Mom bought pints of fruit from Mrs. Picraux, who owned a strawberry farm on Old Colony Road. Dad would sometimes help her with the work of canning the fruit.

Though we had a beehive on the farm, we never took any honey from the bees. For syrup, we made molasses from the sorghum that grew in the little field across the creek from the barn. (Our watermelon vines shared this field with the sorghum.) Before the cane was cut in the fall, my brother and I would help by picking up fallen tree limbs and twigs to fuel the boiling operation. But when the real work began the next day, we were not allowed to go anywhere near the fire.

Mom grew dill, parsley, sage, mint (for tea) and a few other herbs in the garden, but spices were brought from Seib & Wackher’s store, as were kitchen staples like salt, sugar, wheat flour, cornmeal, dried navy beans and black-eyed peas, and coffee beans.

All the cooking was done on a wood-fired stove, which was kept burning all the time, even in the summer. The coffee pot was always on the stove, and water for everyday household use was heated on the stove as well.

Baking was done one day a week. Mom usually made three loaves of crusty yeast bread, a pan or two of cornbread, and the cakes and fruit pies (peach, apple, or cherry) that were to be served at dinner throughout the week. One time I remember Mom baked a coconut crème and a banana crème pie with meringue topping — but I don’t think she did that more than once.

For breakfast, we usually had bacon and eggs; sometimes there were pancakes or homemade donuts deep-fried in lard, or cornmeal mush (prepared the night before), sliced, fried in bacon grease, and served with molasses. The lunch we took to school was the same every day: one sliced pork-and-butter sandwich and one jelly-and-butter sandwich. On days we spent at home, our lunches were much the same.

Preparation for dinner started early every day, with peeling the potatoes and washing the vegetables. Bread and butter were always on the table, as were home-made condiments, pickle relish, jelly and fruit preserves. Sunday dinner was usually chicken and dumplings, gravy, vegetables, and a seasonal dessert. On wash day, there was usually a big pot of beans with a pork bone cooking all day on the back of the stove. Mom was very busy on these days.

The family always ate in the kitchen. The dining room was only used for Sunday company and at times when folks came to help out with seasonal work, like threshing, hog slaughtering, and apple butter making in the fall.

Part VII

Every March, Aunt Ines and Uncle Currier hosted a dinner at their house in Hamburg to celebrate Uncle Currier’s birthday, my parents’ wedding anniversary, my brother’s birthday, St. Patrick’s Day, and Spring. This was the only time I ever saw most of my grandfather’s brothers and sisters together. It was a chance for them all to catch up on family news.

Around the same time of year, some of our chickens became “setting hens.“ They were permitted to “keep” some of the eggs they laid (plus a few extras that Mom would put underneath them to hatch). Fresh straw was provided in all the nest boxes in the laying house, and as we gathered the eggs that the other hens laid there each day, the setting hens were never bothered until the chicks were hatched.

After school was out, once in a while Mom would pack a picnic basket for us to take to the orchard for lunch under a fruit tree. Eating outside was always fun for us kids. An even more fun day was when Dad was home from his out-of-town work, and drove us to the Callaway Fork to have a picnic lunch on the big flat rocks beside the creek. We kids waded in the stream while Mom and Dad relaxed nearby.

We grew lespedeza, a kind of clover, and tall grasses for the cows’ and mules’ fodder. One summer, my brother and I were allowed to go with the men who came to help with the haying, picking up the piles of mown grass to be brought to the barn for silage. It was a terribly hot day. The grasses stuck to us and we were drenched with sweat — in short, we were utterly miserable.

While the men were pitching the hay into the loft, Dad told us we could go to the creek to cool off. We removed our shoes and jumped in before it came to us . . . What will Mom say? But by the time we got back to the house, we were barely damp. Mom didn’t say anything to us about “going swimming” in our clothes.

As I recall, the local wheat harvest always took place in early July. We did not plant wheat, but everyone kept an eye on the sky during the final days before the thresher came, because a severe storm at that time could ruin a crop.

The 4th of July was an important holiday that came during haying time. The VFW in Defiance always held a big celebration with a whole hog barbecue dinner, band music, dancing, and fireworks.

This was a time and place when men running for political office could meet and greet the people of the community. One politician I remember was Earl Sutton. I also remember seeing Uncle Lewis Taylor (Aunt Mollie Keller’s brother), the principal of Francis Howell High School. He always dressed very formally, with a high stiff collar and old-fashioned dark-colored garters over his sleeves.

Another big local event we attended as a family was the annual “homecoming” celebration in Wentzville, held in the summer to raise money for civic improvements, like buying a new fire engine for the town.

When the corn was ripe, it was harvested and put in the corn crib to be used for the animals’ winter food. The pigs ate dried corn off the cob, and their diet was supplemented with kitchen scraps, brought out once a day in a pail and emptied into their feed trough. The chickens were served cracked corn.

Every year in the autumn, Grandpa would take his ax into the woods and mark the trees to be cut down later for firewood. Dad and Mom would also take a walk in the woods together (without us kids) to select the cedar tree that would become our Christmas tree.

We gathered nuts in the fall — walnuts from the trees in our grove, and hickory nuts that we picked up in the woods. For paper-shell pecans, the folks always went to the “bottom” outside Defiance and bought bags of nuts from the owners of a well-known pecan grove.

Hickory nuts could be eaten fresh as they were gathered, but not walnuts. We picked up the big green balls, brought them home, scattered them on the ground, and waited. When they turned black, we removed their husks and cracked them for delicious snacks. Some of the nuts were saved for baking later. It took a while for the black stains on our hands to fade.

Apple butter making was a fall event that always involved people from the community coming to help. The men picked the apples, the kids brought water from the well to wash the fruit, and the women helped with peeling and coring, cooking the apples in a large black kettle, and canning. When I was old enough, I helped with this production, stirring the big kettle while the boiling mass was transformed into thick sweet apple butter. Everyone who helped got to take home a few jars of the finished product by way of thanks.

The apples that were to be kept for eating and for pies were carefully stored in the cellar in baskets filled with straw. After the potatoes were dug in the fall, they too were laid in straw-filled containers to keep over the winter in the cellar.

An important late fall chore was cleaning out the animals’ stalls in the barn. The gathered residue was taken out to the garden, spread over the surface and plowed into the ground to become fertilizer over the winter. (Putting animal waste directly on the garden in the spring would have “burned” the tender young plants.)

One year in the fall, quilting frames were brought to our house and left overnight to be set up for a quilting party the next day. While we were at school, ladies came to quilt and visit with Mom. By the time we got home, the party was over and the frames were all ready to be picked up. I had missed all the fun!

After the first hard frost, people came to help with hog killing. We kids were kept away from the activity, but we heard the gunshots and could well imagine what was going on. Early in the morning, a pit was dug (in the same place every year), and a fire was built in it. A huge container was placed over the fire pit and filled with well water.

Ladies came with covered dishes to help with the lunch. While Mom fed the folks who had come to help, Grandpa personally supervised the activity in the smokehouse. He only used hickory wood for smoking, and he had his own recipe for mixing the spice rub he used to cure the meat.

When the butchering was complete, Dad made sausages. The year before we left the farm, I got to help with this, by scraping the hogs’ intestines (after they had been cleaned out and boiled) for casings, while Dad put the meat, spices and other ingredients into the meat grinder.

Before the men who came to help left at the end of the day, they put out the fires, filled in the pit, and washed the equipment and returned it to the storage shed. Everyone received a piece of meat in return for their help. Those who wanted fresh meat took their piece with them when they went home. Those who wanted smoked pieces had to come back later to get their selection.

About this time of year, Dad and Grandpa would take the crosscut saw into the woods to cut down the trees that had been marked for firewood. Then, after we had our first good snowfall, they took the mules and a sled to bring in the felled trees to the wood lot at the side of the yard.

On Christmas Eve, Dad would go for a walk by himself in the woods and return with the cedar tree he and Mom had chosen to be our Christmas tree. The tree was set up and decorated with ornaments that had been used when Mom was young, and it also had real candles attached to its branches. It was quite a sight when the candles were aglow . . . but kids, dogs and burning candles could not be left alone for long with the tree.

The candle lighting was followed by a special dinner and cake to celebrate our little sister’s birthday. Christmas was always “tomorrow.” Before the candles were put out that night, we kids hung our stockings on the wall behind the tree. The next day, we found treats in them — oranges, bananas, English walnuts, Brazil nuts, hard Christmas candies, and little gifts.

Over the winter, Grandpa would sharpen his tools — the saws, scythes, hoes, axes, and other implements that he kept outside in the shed. By February, the seed catalogues would start to arrive in the mail. It was time to select plants for the garden, and start thinking again of spring.